(Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer, and none of this is intended to be

legal advice. I do, nevertheless, consider myself to be an informed

layman - and offer this analysis as a starting point for research into

the legal status of GIS data in New York, with citations to relevant

law, court cases, and commentaries from both sides of some of the

controversies. I do not purport it to be an unbiased analysis; as and

OSM contributor and otherwise as an ‘open sourcerer’, I have strong

personal opinions regarding the purported ownership of factual

information. I nevertheless attempt to present the law as it stands,

even if I sometimes make the Dickensian observation that “the law is

an ass.”)

What’s up with GIS data in New York?

GIS data originating from government agencies have, for about twenty

years, been subject to considerably uncertainty and risk. This largely

stems from the fact that in many jurisdictions, the mantra that

“government should be run like a business” has led to expectations

that state and local GIS departments should support themselves on user

fees, rather than from the general fund. The most lucrative source of

these fees has been the “multiple listing services” used by real

estate agents to exchange data about houses on the market. These

services often pay handsomely, far in excess of the cost of

reproduction, for the maps of tax parcels. These provide the agents

with the boundaries of properties listed for sale.

It is worth noting that in this discussion, I refer to State and local

data. It has always been held that works prepared for the US

Government by a government employee engaged in the performance of

official duties are in the public domain. Works produced by

contractors, depending on the terms of the contract, may be

protected by copyright. Ordinarily, in this case, the copyright

holder will be identified prominently. Those who use public data

promulgated by a Federal agency have little to fear.

With the advent of broad use of the Internet in the 1990’s, more and

more GIS data belonging to the States have been exchanged in digital

form. This exchange has meant that the cost of reproduction has fallen

to nearly nil, and the sale of such data is openly meant to defray the

cost of the original work. The courts have had a mixed reaction to

this, and the way that it tends to come into apparent conflict with

the Freedom of Information laws passed in the various states.

For data belonging to the counties, New York State endures a

particularly murky legal situation. In particular, Suffolk County was

a bellwether in attempting cost recovery for its production of the tax

maps.

The Suffolk County case - origins

In 1971, the county separated its Real Property Tax Servicce Agency

from its Department of Public Works, and provided a USD2.8 million

initial funding resource in the form of a cost transfer from Public

Works for the preparation of the tax maps. At the time, the maps were

drawn by skilled drafters in pen and ink on plastic film. In 1974, the

first edition of the tax maps was completed, and the county filed for

copyright registration on the maps.note-1 Upon securing the copyright, the county commenced

negotiatons with Real Estate Data, Inc. (REDI) to reproduce the maps

in paper form and market them to the general public. The eventual

agreement resulted in a USD25,000 annual payment from REDI to the

county, an additional payment of 5% of REDI’s gross sales, and a

promninent display of Suffolk County’s copyright notice in every

edition of the maps.

In the early 1980’s, REDI changed corporate control several times. As

a result, the court papers variously refer to REDI, Information

Systems and Services, Inc., Thomson-Ramo-Wooldridge (TRW), Experian

Data Services, First American Real Estate Solutions, and possibly

others. (Astute readers will note that several of these names are

associated with one of the ‘big three’ US credit-reporting

bureaux. The corporation was unsympathetic defendant even at the time

of the court case discussed here.) After one of its changes of

control, the agreement allowing it to copy and distribute tax maps was

abrogated or allowed to lapse. The specifics are unclear, but all

parties substantially agreed that no agreement was in force by the

mid-1980’s.

With no agreement in force, REDI continued to sell copies of the maps,

but no longer received updated information from the county. The county

was concerned both about the loss of revenue and the complaints that

it received about obsolete maps, and in 1999, filed suit against

Experian for declaratory and injunctive relief, and for monetary

damages for copyright infringement. The cited article

note-2

details a timeline of the case.

The Suffolk County case - the defense

Experian offered no argument, at least in the initial proceedings,

that it had not made and distributed copies of the tax maps. Instead,

it moved to dismiss the case, on the theory that as a matter of both

public policy and law, the county could not own a copyright on the

maps. The US District Court for the Southern District of New York

disagreed, and ruled that nothing in US copyright law forbade a State

or local government, as opposed to the Federal government, from

registering, owning and prosecuting a copyright.

Experian moved for reconsideration, and presented the argument that,

while Federal law might not forbid a State from enforcing a copyright

in its documents, New York’s Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) did

forbid it. It cited advisory opinions offered by the New York State

Committee on Open Government note-3 (and the court cases

referenced therein) that argued that failing to disclose the tax maps

or requiring contracts restricting their public redistribution ran

against the FOIL. Upon analysis, the court agreed, and dismissed the

county’s case. The county appealed.

The Suffolk County case - the decision

The Second Circuit court of appeals decided the case, issuing its opinion on 25 July 2001. note-4

Since the ruling was on a motion to dismiss, there was no finding of fact.

All of the court’s opinions are on matters of law.

The defendant’s first argument was that the county had failed to state

a claim. As the court observed, “The issue is not whether a plaintiff

will ultimately prevail but whether the claimant is entitled to offer

evidence to support the claims” - construing all the facts in the light

most favorable to the claimant.

The court found that the Copyright Act of 1909 had no restriction on

state’s asserting copyright over their works for hire. (For example, a

state or local government, could commission a piece of public art, and

retain copyright over it if it was contracted under a work-for-hire

agreement.) The tax maps could be “original works of authorship” and

protectable under copyright.

Copyright law requires that copyright be claimed over an “original

work of authorship.” Bare facts that do not originate with the author

of the work do not qualify, and the “sweat of the brow” in compiling

them does not by itself imbue them with originality. Rather, a work is

copyrightable only if “it possesses at least some minimal degree of

creativity.” note-5 First American had

argued that the tax maps contained no original protectible elements,

and in the alternative, argued that any original elements were not

subject to copyright protection befcause they were dictated by state

law and regulations. Suffolk had responded that “tax maps contain a

substantial amount of original material, research, compilation and

organization wholly original with the plaintiff.”

The court found that it needed to focus on “the overall manner in

which [the plaintiff] selected, coordinated, and arranged the

expressive elements in its map, including color, to depict the map’s

factual content.” (What this focus means in the context of GIS data is

surely not clear to me!) It found that Suffolk’s allegation was

sufficient to present a question of fact for a jury to decide. Alas,

its phrasing was atrocious: “The District Court thus correctly found

that Suffolk County has sufficiently alleged that its work is

protected.” (More on this later!)

The defense had also presented the argument that New York’s FOIL

abrogated Suffolk’s copyright, The State also intervened as amicus

curiae, asserting its interest in the open sharing of the maps. In a

lengthy argument, the Court concuded that the statutory language of

FOIL was in fact silent as to the operation of coyprights. It further

concluded that the advisory opinion of the Committee on Open Government

should be accorded no deference, since it was advising on the operation

of Federal copyright law (over which the Committee had no advisory power)

and not on the State’s FOIL (which had already been dispensed with as

being silent on copyrights).

Finally, the defense had argued that the tax maps were in the Public

Domain from their inception. They are edicts of government, the

defense argued, by analogy to legislative statutes and judicial

opinions. The court found that the determination turns on two

considerations: whether the entity that created a work needs an

economic incentive to create or has a proprietary interest in creating

the work, and whether the public needs to have notice of a particular

work in order to have notice of the law. The court found the first

consideration to be a matter for the trier of fact - the county was,

at the very least, entitled to present evidence that the economic

incentive of copyright was necessary for the maps’ creation. The

court found the ‘fair notice’ concern to be irrelevant, since any

individual required to pay property tax surely had access to both

the law and the relevant map.

What was left, therefore for the District Court to decide was the the

extent to which the tax maps were original (rather than compilations

of fact with decisions guided strictly by regulation), and, should

they be found to be original, the extent to which the economic

incentive of copyright was needed as an incentive for their

creation. It remanded the case to the District Court for further

proceedings consistent with the opinion.

Following this judgment, the parties settled. As far as I know, the

settlement terms were undisclosed. (If that is the case, an argument

could be advanced that the failure to disclose them could itself be a

violation of FOIL.)

The aftermath of Suffolk County

The state government has continued to assert that Suffolk County’s

position is inconsistent with the Freedom of Information Law and the

Federal copyright law, correctly pointing out

that certain relevant facts were never determined by the lower court:

On appeal, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held that in general,

New York State, local government, and Suffolk County may claim a

copyright protection under the Copyright Act. In contrast to the

Federal Government, which is prohibited from obtaining copyright

protection for its works (17 USC §105), the Second Circuit found

that “the Copyright Act is silent as to the rights of states or

their subdivisions” and that “[b]y specifying a limitation on

ownership solely against the federal government, the Copyright Act

implies that states and their subdivisions are not excluded from

protection under the Act.” County of Suffolk v. First American Real

Estate, 261 F.3d 179, 187 (2nd Cir. 2001).*

Due to insufficient evidence, however, the Second Circuit remanded

the matter concerning whether the maps were sufficiently original

and creative to qualify for copyright protection, or whether the

content and the form of the maps were dictated by state law and

regulation and thus not subject to copyright protection. Further,

the Second Circuit opined, it would be for the District Court to

determine whether the tax maps were in the public domain from

inception, and thus outside the coverage of the Copyright Act. To

make this determination, the District Court would have to consider,

most importantly, whether the County needed the economic incentive

of the Copyright Act to create the maps, or whether it had adequate

incentives or obligations to produce their respective materials.

The Committee further went on to advise:

Conditioning the release of copies on contractual agreements

governing future treatment of the copies, in our opinion, would

thwart the very purpose and intent of the Freedom of Information

Law. It is our belief that when materials are accessible under the

Freedom of Information Law, upon receipt of the appropriate fee,

they must be released to the applicant without

restriction. Accordingly, in keeping with the Second Circuit

decision in County of Suffolk, we advise that it is permissible for

the County to notify the applicant that the materials may be subject

to copyright protection, but that the County cannot condition access

on a contractual obligation pertaining to redisclosure of records

accessible to any member of the public.

and the opinion also addresses the fact that it is impermissible to

use reproduction fees to cover anything but the cost of reproduction:

… although compliance with the Freedom of Information Law involves

the use of public employees’ time, the Court of Appeals has found

that the Law is not intended to be given effect”on a cost-accounting

basis”, but rather that “Meeting the public’s legitimate right of

access to information concerning government is fulfillment of a

governmental obligation, not the gift of, or waste of, public funds”

[Doolan v. BOCES, 48 NY 2d 341, 347 (1979)].

note-6

It has continued to issue advisory opinions of a

similar nature as recently as 2015. note-7

Nevertheless, much of the press had taken the Suffolk County

decision as a statement from the Second Circuit that tax maps are

protected by copyright (a decision that it never reached). In fact, I

vaguely recall a case from about a decade ago (to which I have mislaid

the citation) in which New York City asserted similar claims against a

copyright defendant, and the lower court took as given the misreading

that tax maps are protected by copyright, finding the defendant liable

on the pleadings, since the fact of copying was uncontested. (The case

was mooted before an appeal could make its way through the system by

the passage of New York City’s Open Data

Law note-8).

Most New York counties, in this legal situation, continue jealously

to guard their cadastral data in the hopes someday of securing significant

cost recovery through licensing revenue.

What does all this mean for OSM’s use of New York Government data?

Despite all the legal turmoil, the prospect for using New York government

data in OSM is actually fairly bright.

Data produced by and for the New York State government and listed in

the gis.ny.gov data catalogue are pretty

much fair game. The state government has consistently held for more

than two decades that its data are public (with certain narrow

statutory exemptions related to confidentiality and homeland security)

and that they are free to all comers. Occasionally, the agency that

produced an specific data set will request acknowledgment as a

courtesy, and we can certainly satisfy that request on

the Contributors

page.

New York City’s data are also fair game, owing to the sweeping scope of

its Open Data Law, which also leaves little room for the city to escape

its obligation to make its operational data open and free to share.

Cadastral data, and data in general from the individual counties apart

from New York City, is a mixed bag. The state has requested that the

counties make parcel data available, but the response from the

counties has been slow. As of this

writing, 21 counties have resolved to

make their tax parcel data public.

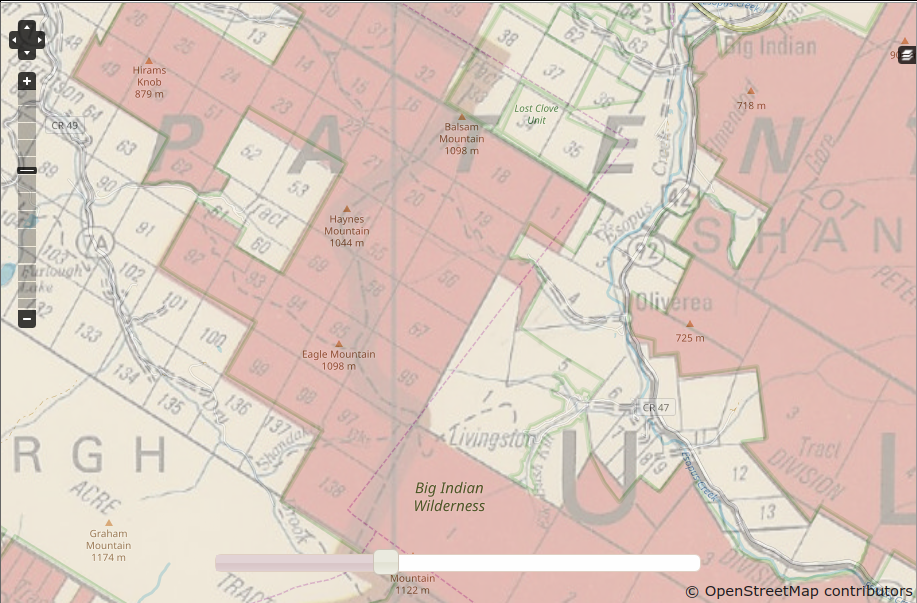

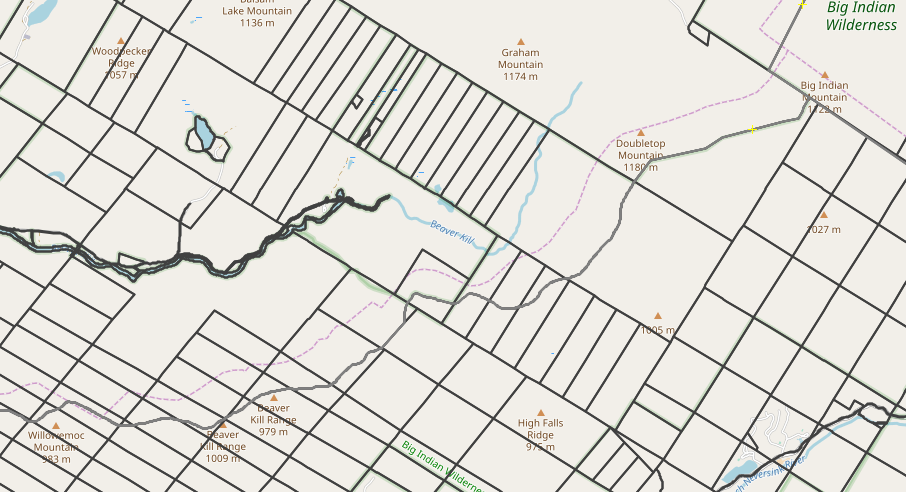

In addition, New York State has asserted that it has an unquestioned

right to publish data about the parcels that it owns in allodium. (New

York is the sovereign; it cannot own parcels in ‘fee simple’ since there

is no superior title to which it answers.) It therefore publishes state-owned

parcel data for all 61 counties.

I had previously had reservations about the legality of importing New

York’s

address point data because

the address points were supplied by the counties, and in many cases

were derived from parcel centroids. (If the parcel boundaries, devoid

of other metadata, are the subject of copyright, why not their

centroids?) I therefore counseled that people should proceed with

caution in the forty counties that have not agreed to share their

parcel data. My fears have been dispelled by a recent e-mail sent by

Frank Winters to an OSM contributor, confirming that the data may be

used without restriction or license for any lawful purpose. We can

safely presume that the state government would not offer rights

that are not theirs to give.

We should, as a project, retain a copy of Mr Winters’s e-mail including metadata, against any future inquiries regarding the data from gis.ny.gov. What is a proper repository for this messsage?

Given the legal uncertainty, extreme caution is still needed for county and municipal data outside

New York City that have not been blessed by NYSGIS!

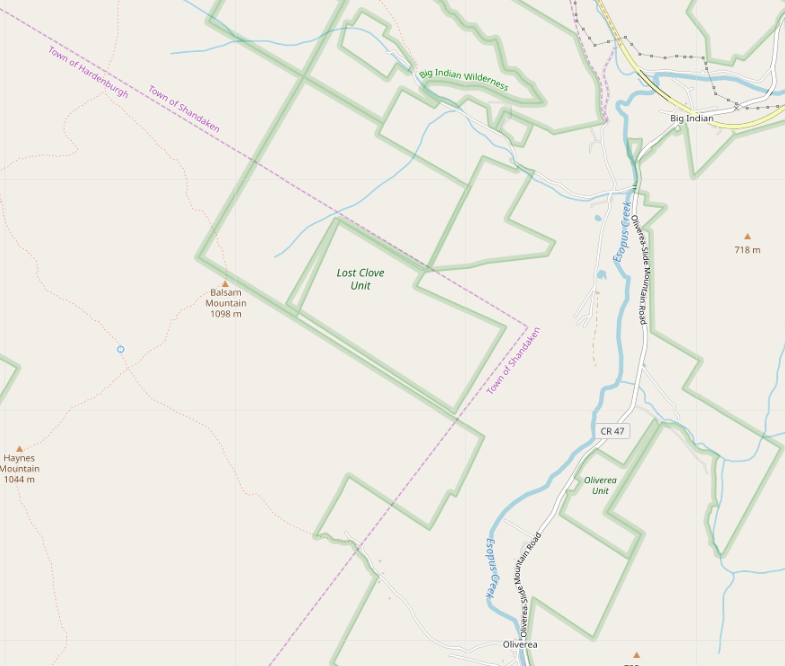

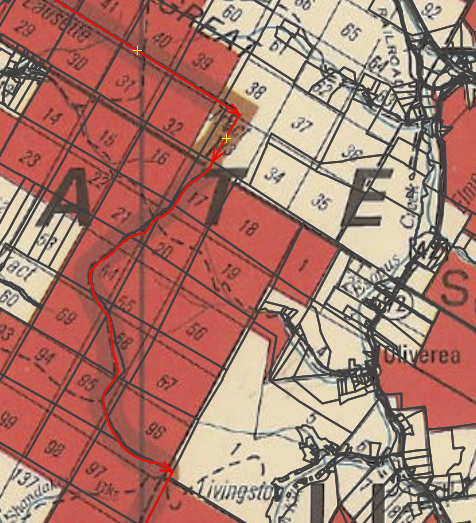

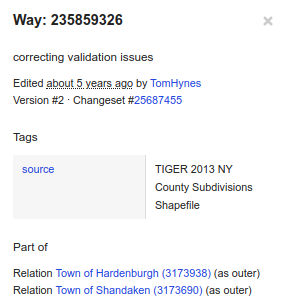

People searching OSM contributions for my user name (ke9tv) will find

the occasional parcel of public land in which I cite ‘XXX county tax

rolls’. In all such cases, either the given county is one of the 21

that have given permission, or the tax rolls were used as one of

multiple data sources in an effort to resolve boundary

inconsistencies. In all cases where the tax rolls were consulted, the

parcels were redrawn before uploading and there will be at least

hairline differences between OSM’s copy and the county’s. Nothing

remains of any artistic decisions made by the person who produced the

original map. Nor does anything remain of the selection, sequence and

arrangement of the data, since only individual parcels were extracted

and any selection was mine alone. Since US law recognizes no copyright

on the bare facts, I believe myself to be on an entirely firm legal

footing.

Notes

note-1. note-2. Most of the factual account of the

prosecution history of the case derives from Penny Wells

LaValle,

Tax Maps and the Legend of the Dragon Slayer. _Geographic

Information Systems Technology News 3:_2 (Fall/Winter 2001).

note-3.

The

New York State Committee on Open Government

has a name that sounds as if it might be an NGO, but it is in fact an

agency of the Department of State responsible for overseeing and

advising the government, the public and the media regarding New York’s

Freedom of Information,

Open Meetings,

and Personal Privacy Protection

Laws.

While its opinions are advisory in nature, the Executive Branch offers

them extreme deference (partly because most members are members of the

administration; the Lieutenant Governor, the Secretary of State, the

Director of the Divison of Budget and the Commissioner of the Office

of General Services serve ex officio; four more members are

appointed by the Governor, while one member is appointed by each house

of the State Legislature). The opinions may be presumed, absent evidence

to the contrary, to be the official policy of the State.

County and local governments, as we see here, are more inclined to

reject the Committee’s advice and challenge it in court, as we see

here.

Relevant opinions presented to the District Court in relation to the

Suffolk County case include:

-

Robert J. Freeman, Executive Director, New York State Committee on

Open Government, letter to Kenneth W. Lovett, President, Virtual

Information Systems, Inc., 5 January 1993

FOIL-AO-f7507.

(opining that the contents of a GIS system are “statistical or

factual tabulations of data” and thus not exempt from FOIL)

-

Robert J. Freeman, Executive Director, New York State Committee on

Open Government, letter to Kenneth W. Lovett, President, Virtual

Information Systems, Inc., 7

May 1997. FOIL-AO-f10072

(specifically opining that Suffolk County’s practice of charging a

reproduction fee of USD4.00 per map was both in excess of the cost

of reproduction and inconsistent with the FOIL, and moreover

advising that the county could not skirt the issue by invoking the

“unless a different fee was established by law” exception, since a

mere committee of the county legislature did not have the power

under statute to impose such a fee.)

-

Robert J. Freeman, Executive Director, New York State Committee on

Open Government, letter to Robert N. Brower (Cayuga County Planning

Board), 29 December 1998

FOIL-AO-f11230.

(advising that the FOIL may require transmission of computer records

in machine-readable form, while not requiring that new software be

developed or new data entry conducted to produce such records, and

urging that the Legislature consider adding language to the FOIL to

require that computer databases be designed to provide easy

redaction of private or security-sensitive information, so that FOIL

requests can be answered without reprogramming.)

note-4

County of Suffolk, New York, v. TRW. 261 F.3d 179 (2001).

note-5

Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv., Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991)

note-6

Camille S. Jobin-Davis, Assistant Director, New York State Committee on Open Government, letter to [redacted recipient], December 19, 2005 FOIL-AO-15695

note-7

Robert Freeman, Executive Director, New York State Committee on Open Government,

e-mail to [redacted], 6 February 2015 FOIL-AO-19246

note-8

New York City Local Law 11 of 2012.

note-9

Frank Winters (Geographic Information Officer, New York State Office

of Information Technology Services), e-mail to Skyler Hawthorne, 17 July 2021,

copy (with metadata) mirrored at https://kbk.is-a-geek.net/attachments/20200719/winters_20200717.txt